Freeman’s | Hindman and the Philadelphia Art Museum: A Century-Long Partnership Renewed

Freeman’s | Hindman is honored to present several important works deaccessioned from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (recently renamed the Philadelphia Art Museum) in its upcoming Fall fine art auctions.

Earlier this year, the Museum’s Board approved the deaccession of a select group of works to support the institution’s broader goals: advancing public engagement, fostering meaningful access to its collection, and ensuring the sustainability of its holdings for future generations. Three of these works will be offered across Freeman’s | Hindman’s Fall auctions, thus continuing a partnership between two storied Philadelphia institutions whose shared history extends for more than a century. Founded in 1805, Freeman’s is America’s oldest auction house, while the Museum traces its origins to 1876 and the Centennial Exhibition that first established Philadelphia as a center of artistic innovation and exchange.

Leon Underwood’s Negro Rhythm: A Study in Movement and Modernity

A highlight of the October 28 Impressionist and Modern Art auction will be Negro Rhythm: Harlem, N.Y., a dynamic bronze sculpture by British artist Leon Underwood, which entered the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection in 1962.

Born in Shepherd’s Bush, London, in 1890, Underwood was a sculptor, painter, and teacher whose impact has been more deeply appreciated posthumously than during his lifetime. A restless traveler and scholar, he immersed himself in non-Western art traditions (African, Mexican, and Native American) which profoundly shaped his understanding of form and movement. His 1934 publication Art for Heaven’s Sake was among the first English-language works to advocate for African art as a complex and spiritual tradition, rather than a purely ethnographic curiosity.

Underwood’s fascination with rhythm and vitality translated directly into his teaching at the Brook Green School of Art, where he urged his students to draw from life models in motion, capturing not stasis but the pulse of life itself. Negro Rhythm embodies this philosophy. Art historian Christopher Neve described the sculpture as “an inspired scribble in the air, the patinated bronze as compulsive as a 12-bar chorus from New Orleans with its insistent syncopated beat... the whole object, twenty-two inches high, an inspired exercise as vividly period as Edith Sitwell’s allegro negro cocktail shaker.” With its sinuous energy and spiraling form, the dancer seems to pivot around an invisible axis, crystallizing Underwood’s lifelong quest to express the movement of the human spirit through sculptural form.

A Vision of Splendor: Hondecoeter and de Coninck

Two magnificent still lifes will take center stage in Freeman’s | Hindman’s 19th Century European Art & Old Masters auction on November 4 in Philadelphia. Both exemplify the grandeur and refinement of seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting, as well as the complex histories of authorship and collaboration that continue to intrigue scholars today.

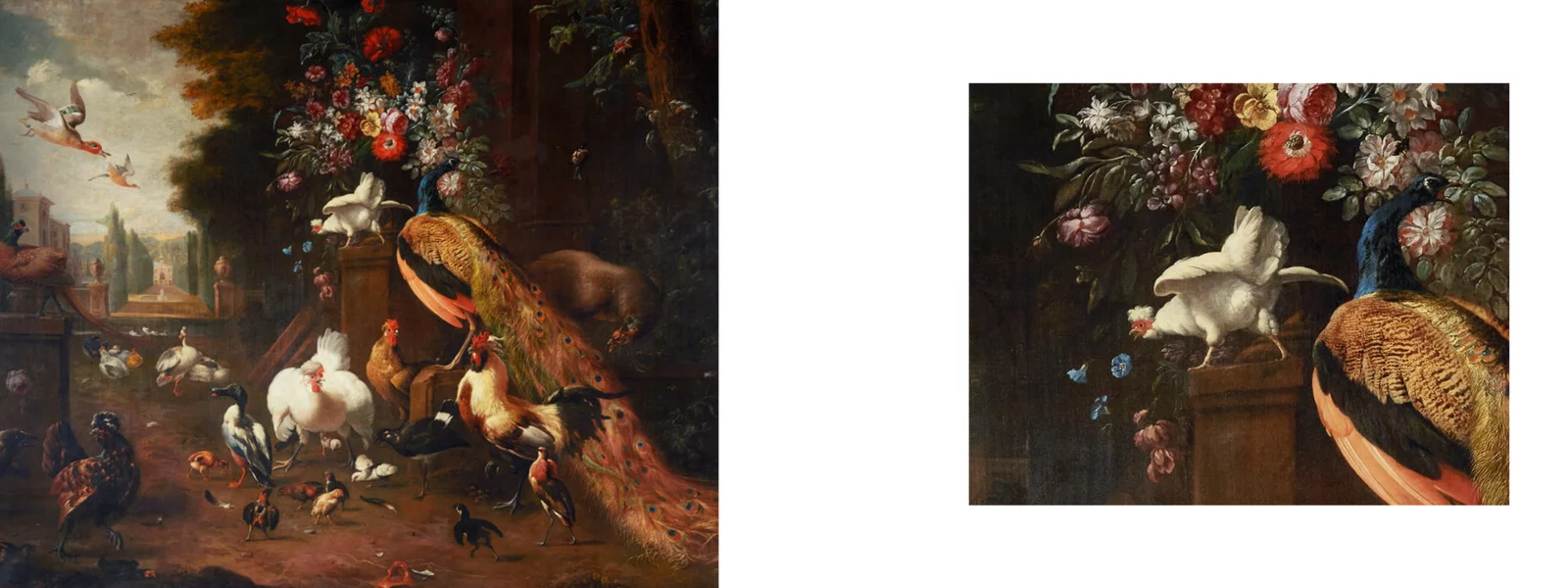

The Poultry Yard: After Hondecoeter

This large and lively Poultry Yard reflects the enduring appeal of Melchior d’Hondecoeter’s celebrated bird scenes, which set the standard for Dutch animal painting in the late seventeenth century. The composition, featuring a peacock, rooster, and a lively array of domestic and exotic fowl, derives closely from d’Hondecoeter’s Revolt in the Poultry Coop(Hamburger Kunsthalle) and other known variants.

However, the Philadelphia version reveals intriguing differences. Enlarged along the left and lower edges, and showing clear variations in handling between the central and peripheral figures, the work likely emerged from a collaborative or workshop context. Correspondence from 1990 between the Museum and Dutch scholar Fred Meijer proposed that the exuberant floral passages were painted by Philip van Kouwenbergh (1671–1729), a still-life specialist who often borrowed motifs from d’Hondecoeter’s compositions. The delicate blossoms and luxuriant vegetation indeed align with Kouwenbergh’s style, while the birds themselves repeat signature Hondecoeter motifs (such as the cluster of chicks in the foreground, echoing the Seven Chicks study now in the Rijksmuseum).

Whether executed collaboratively or entirely within Kouwenbergh’s studio, the painting captures the diffusion of Hondecoeter’s imagery in the decades after his death, as his spirited barnyard scenes continued to inspire new interpretations for an eager collecting public.

The Pronk Still Life: Andries de Coninck

Equally sumptuous is a grand Pronkstilleven still life long attributed to Jan Pauwel Gillemans, now convincingly reattributed to Andries de Coninck (active 1643–1659). With its gleaming silverware, vibrant lobster, and array of musical instruments, the painting epitomizes the opulent still-life tradition developed in mid-seventeenth-century Antwerp.

Recent scholarship by Professor Fred Meijer identifies the signature and date as later additions, instead linking the work to de Coninck, one of the earliest Antwerp painters to reinterpret Jan Davidsz. de Heem’s lavish banquet scenes on a more intimate scale. Here, the central lobster perched atop a wicker basket serves as a compositional anchor, drawing the viewer’s eye through the surrounding fruit, glass, and reflective metal. Subtle chiaroscuro, a restrained palette, and de Coninck’s characteristic attention to texture—seen in the curling sheet of music, the half-filled goblet, and the glistening fruit—imbue the work with both grandeur and quiet melancholy.

Beneath its surface splendor, however, lies a meditation on transience. The overturned glass, the drooping vine, and the fading light remind us that earthly pleasures are fleeting. In uniting opulence and impermanence, de Coninck transforms luxury into allegory: a feast suspended between abundance and decay, beauty and its inevitable passing.

"I have always considered the Philadelphia Museum of Art as one of my favorite museums, so so I am particularly pleased that we will be offering these two magnificent Dutch 17th-century paintings. It’s impossible not get drawn to both works for their richness of detail and elaborate compositions. While many Dutch paintings of this period are modest in scale, these two are remarkable for their ambition and visual complexity." -David Weiss, Senior Vice President, Fine Art