Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 84

Sale 6465 - Printed and Manuscript Americana

Jan 29, 2026

10:00AM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$20,000 -

30,000

Price Realized

$64,000

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

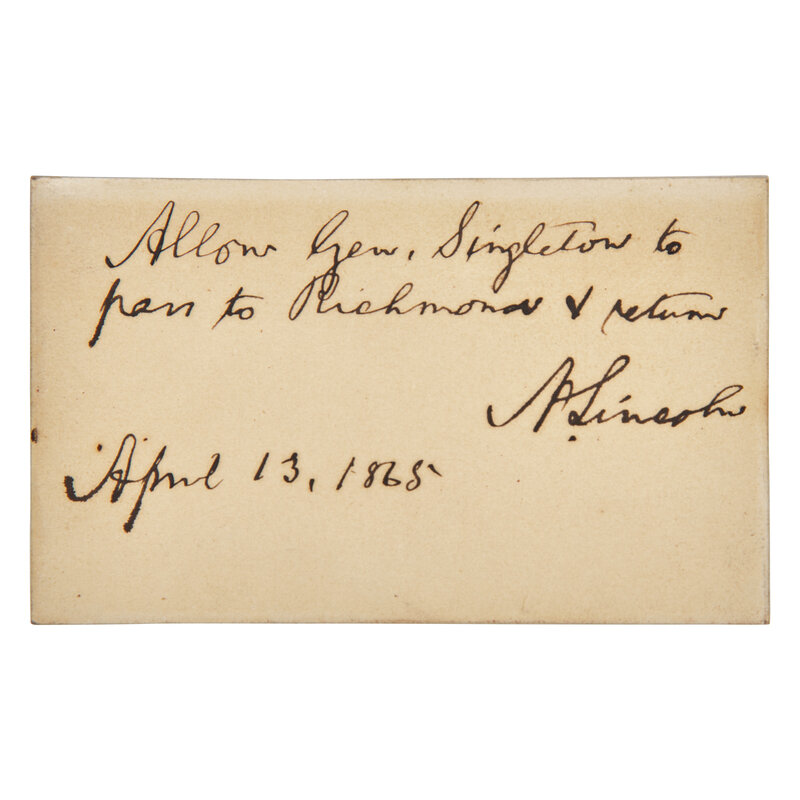

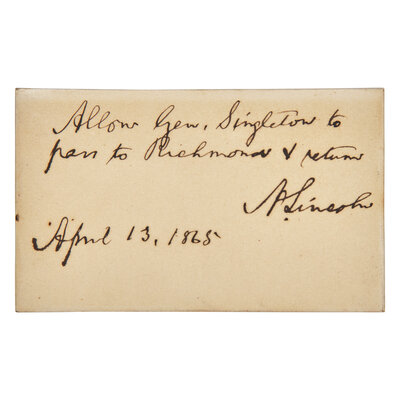

[Lincoln, Abraham] Lincoln, Abraham. Autograph Note, signed

One of the Last Documents Written by President Abraham Lincoln, Penned the Day Before He Was Assassinated

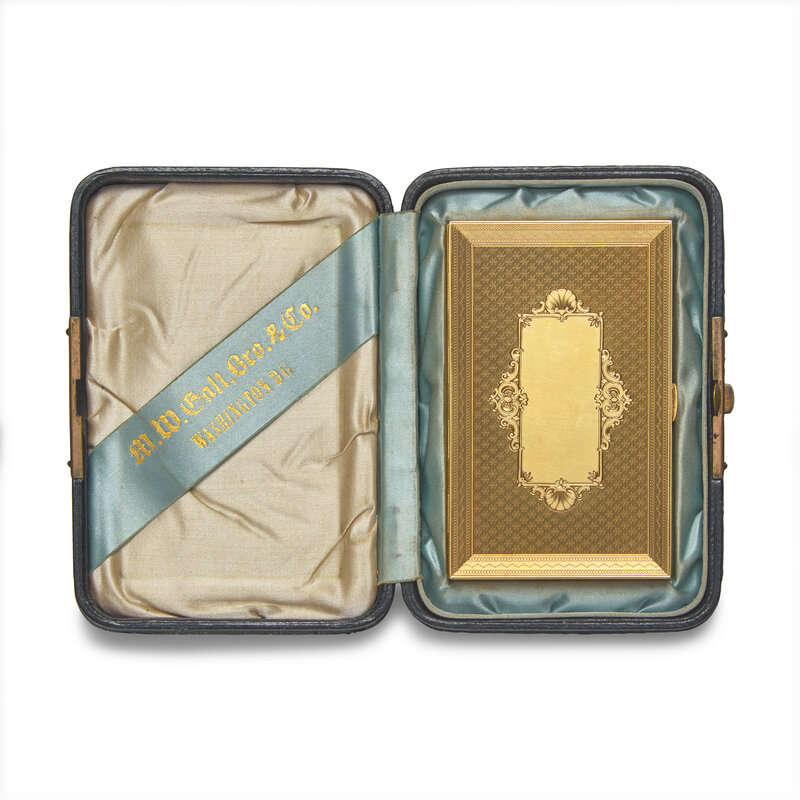

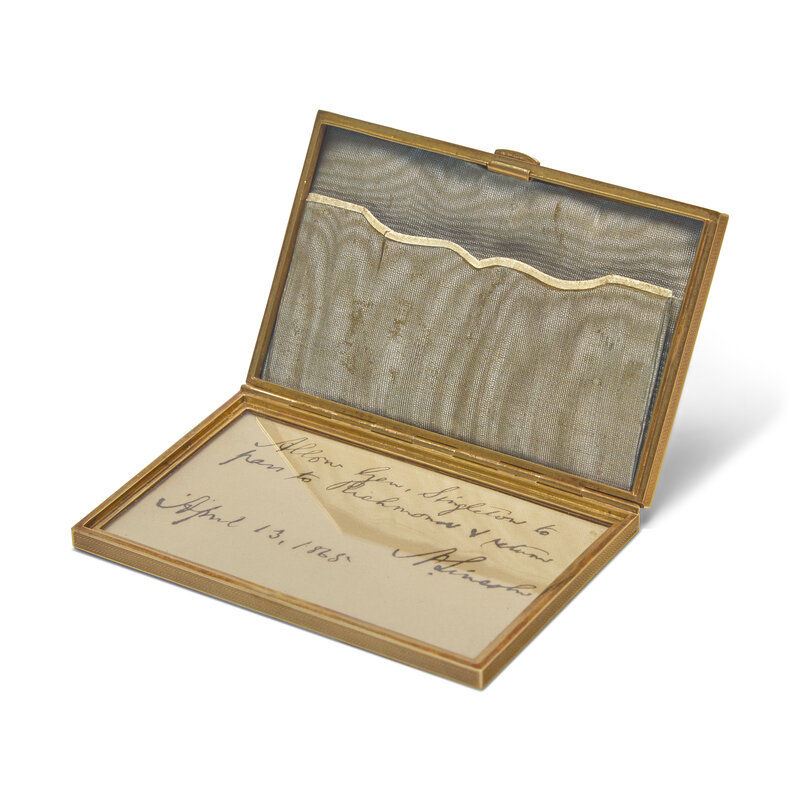

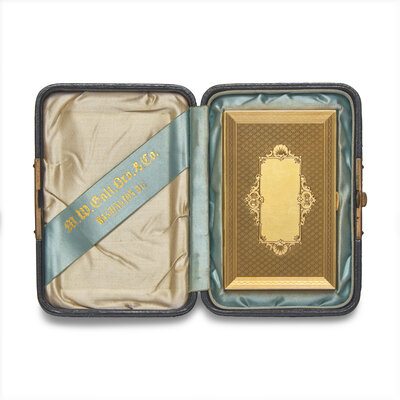

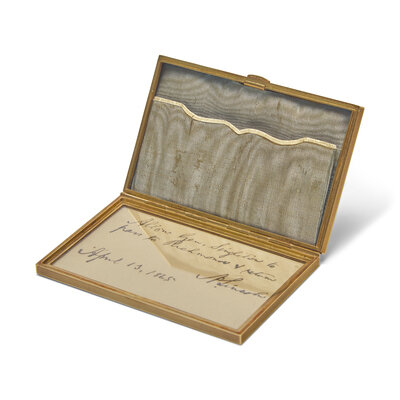

(Washington, D.C.), April 13, 1865. Single oblong card, 2 1/8 x 3 3/8 in. (54 x 86 mm). Autograph note, signed by Abraham Lincoln as President, being a pass for General James W. Singleton to travel through Union lines into Richmond, Virginia: "Allow Gen. Singleton to / pass to Richmond & return / A. Lincoln / April 13, 1865". In contemporary custom solid 18kt gold box (74 dwt), and in original silk-lined leather case, by M.W. Galt, Bro. & Co. Washington, D.C. Basler 8: 410

On the eve of his assassination, President Abraham Lincoln writes a pass for General James W. Singleton, authorizing him to travel through Union lines to Richmond, Virginia to purportedly help restore that state to the Union.

Acquaintances since the 1840s, like Lincoln, the Virginia-born Singleton rose in politics in Illinois under the Whig platform. During that party's dissolution in the late 1850s, each man diverged in their political affiliations, with Lincoln joining the ascendent Republicans, and Singleton the Democrats. The outbreak of the Civil War saw Singleton, whose brother served in the Confederate Congress, become a leader of the Peace Democrats (Copperheads), Lincoln’s northern political foes who sought an immediate end to hostilities and a negotiated settlement with the South. Despite this, during the 1864 presidential election Singleton declined to support Democratic presidential candidate George McClellan, a decision that, coupled with Union victories in Atlanta and Mobile, helped secure Lincoln's reelection.

Union military campaigns toward the end of 1864 and in early 1865 coincided with official and unofficial attempts by Lincoln and others to negotiate an end to the bloody four-year war. Singleton was one such actor who pursued this goal in an informal manner that mixed political intrigue and commercial pursuits. Despite their political differences, but likely due to his connections and influence in the South, Lincoln allowed Singleton to convey messages and conduct informal peace talks with Confederate leaders. First, in the fall of 1864 in Canada, and then in Richmond, Virginia beginning in early 1865. Singleton's peace-seeking motives were interwoven with financial incentives, in particular the opportunity to purchase Southern cotton and tobacco for resale to Northern merchants and Treasury officials at a high profit. He secured his first pass from Lincoln in early January 1865 through an intermediary and mutual friend, United States Senator from Illinois, Orville H. Browning (who was also an investor in Singleton's budding commercial enterprise). Singleton traveled south in mid-January and apparently met with Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and other Confederate leaders to discuss peace terms, and at Lincoln’s direction, to correct them on their belief that the war-weary northern populace had turned against Lincoln. While there was widespread belief that the Southern people sought peace, the negotiations faltered on the issue of slavery and reconstruction, but the door was left open for future talks. Despite the mission's lack of immediate success, Lincoln was apparently pleased with the business contracts Singleton developed, totaling nearly $7 million. Lincoln believed that such trade would help financially strapped Southerners, increase Southern desire for reunion, forestall foreign recognition of the Confederate government through the availability of cotton, and thus put pressure on Confederate leaders to end the conflict.

By the spring of 1865, Singleton was managing the complexities of his commercial venture. Despite Lincoln's apparent blessing of his scheme, rumors of illicit trade and smuggling with the Confederate Army alarmed General Ulysses S. Grant, who disapproved of the trade permits. At that time he wrote to Secretary Seward, expressing his distrust, stating, "I believe there is a deep laid plan for making millions and [Singleton] will sacrifice every interest of the country to succeed." Grant then prohibited all trade across Federal lines until the cessation of hostilities, leaving Singleton's cotton stock and other goods to languish in Richmond warehouses and elsewhere.

The fall of Richmond in early April 1865 brought unrest and disorder to that city, as well as the destruction of Singleton's goods. Seeking to assure the remaining city leaders and citizens that order would soon be reestablished, Lincoln apparently tasked Singleton "to travel quietly to inform the Southerners that the assurances of Executive protection for the reassembling of the Legislature and the consequent restoration of Virginia would be redeemed" (Starr, "Lincoln and James W. Singleton", in Further Light on Lincoln's Last Day..., p. 75, 1930). On April 13 Lincoln penned this very pass for Singleton to again travel through Union lines, and at some point "handed Singleton a letter stating that if Virginia or any of the other southern states would recognize the authority of the United States and elect Senators and Representatives, such members would be entitled to take their seats." (Starr, p. 76). Recounting to a reporter years later, Singleton stated (in the third person), "General Singleton had a conversation with Mr. Lincoln. The latter told him to go to Richmond and assure the people of Virginia that he would favor the return of the state into the union with her government intact, and the same on the part of all the seceded states. It was answered by General Singleton that General Weitzel was now in command; that the Virginia legislature had attempted to follow out this advice, and had been forbidden to do so by a local commander. He complained to Mr. Lincoln that the assurances made to the Virginians had not been carried out, to which the latter replied: 'I cannot do everything at once, for I am impeded by the fact that everything is under martial law at the present time. I wish you to go again, immediately, to Richmond and reassure the people.'"

Whether Lincoln met with Singleton on April 13th or 14th, or on both days, to give him this pass, the possible papers, and to receive instructions, is uncertain. In the aforementioned interview with the Chicago Times in 1885, Singleton stated that this meeting occurred on the 14th, the day of Lincoln's assassination. Historian John William Starr, after reviewing Singleton's papers and other sources states, "It seems clear to me that at some time on April 14th Singleton must have seen Lincoln, but as to whether it was the morning or afternoon I am undecided; certainly it was not the evening." (p. 85). Reviewing the matter, historian Peter J. Barry writes, "The reference to April 14 may actually be April 13, 1865. Years later, Singleton's April 13, 1865 pass from Lincoln became the subject of friendly controversy about official and nonofficial transactions by Lincoln on the last day of his life. Matthew Paige Andrews and Singleton's daughter Lily, had become convinced that Singleton and Lincoln had met again on April 14, after the noon cabinet meeting. The purpose of the meeting was to finalize the plans for Singleton's discussions in Richmond with surviving leaders of the Virginia government. However, no such meeting on the 14th was documented, and Lincoln scholar John W. Starr remained skeptical." (p. 216, Barry, General James W. Singleton: Lincoln's Mysterious Copperhead Ally, 2011)

Lincoln's assassination at Ford's Theatre the night of April 14 prevented Singleton from executing his mission. In a letter to his wife, penned on April 16, the morning after Lincoln's death, Singleton lamented, "Before this reaches you the sad news of the melancholy death of Mr. Lincoln will have been received. I scarcely know how to express my deep sorrow for him personally and for our distracted country...My intercourse with him for the past six months has been so free, frequent, and confidential that I was fully advised of all his plans, and thoroughly persuaded of the honesty of his heart and the wisdom of his humane intentions...I have two cards, one written the day before his death and the other a short time previous, which I shall put into small gold frames to be preserved for my children." While Singleton hoped to be chosen as one of the emissaries to transport Lincoln's body on its multi-state journey back to Springfield, Illinois, he was eventually not selected, and he traveled back to Illinois alone, where he later served as a Congressman representing Illinois' 11th district.

Following Singleton's death in 1892, his wife, Parthenia (1823-1902) became this relic's steward, which was then passed on to their daughter, Lily Singleton Thomas Osburn (1875-1942). Around 1905 it was reported to be in the possession of Civil War veteran and book publisher, Jacob E. Barr (1842-1924) of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who in 1905, purportedly sold the document through his brother, Lancaster bookseller, Charles H. Barr (1848-1918). Contemporary newspapers reported that negotiations were then underway to sell the document to a "known relic hunter". That individual is likely the next recorded owner, Philadelphia banker and collector George C. Thomas (1839-1909). Upon Thomas' death a few years later, it sold in these very rooms in 1924 as a part of the sale of Thomas’ collection. From there it came into the possession of Philadelphia businessman and publisher John Gribbel (1858-1936), and was then sold in his multi-part sale at Parke-Bernet in 1941. It was purchased at that sale by the family of the current owners, in which it has since descended.

According to Roy P. Basler in his Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln this is one of only five passes Lincoln wrote on April 13 and 14. Furthermore, it is one of only around two dozen known signed or penned documents by him in the two days leading up to his assassination the night of the 14th. As most of the documents or letters by Lincoln from the last days of his life are now in institutional collections, or are no longer known to survive, they are extremely rare to market. In the past 45 years, we locate less than 10 documents dated April 13 or 14 and signed by Lincoln that have come to auction, least of which one that held such potential consequences for post Civil War Reconstruction.

This lot is located in Philadelphia.