Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 29

Sale 6465 - Printed and Manuscript Americana

Jan 29, 2026

10:00AM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$150,000 -

250,000

Price Realized

$563,200

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

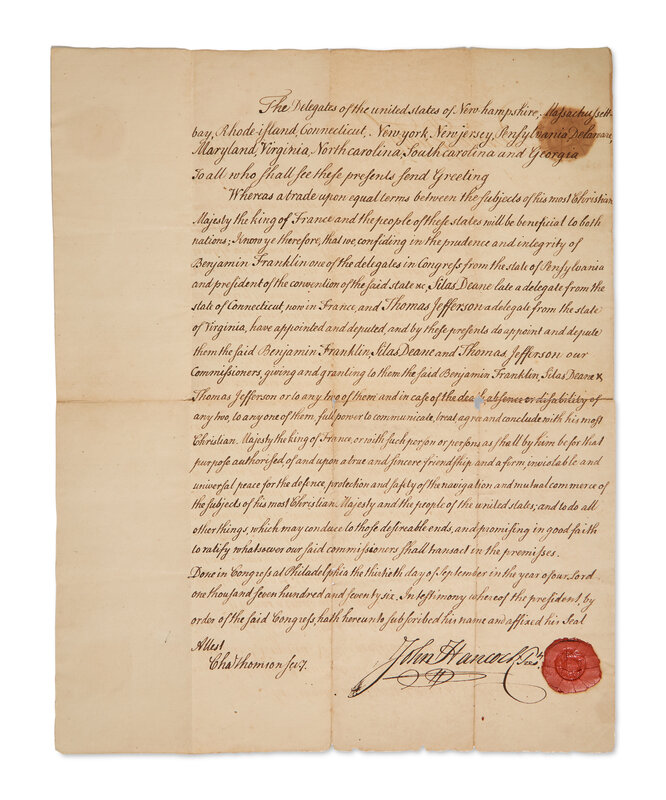

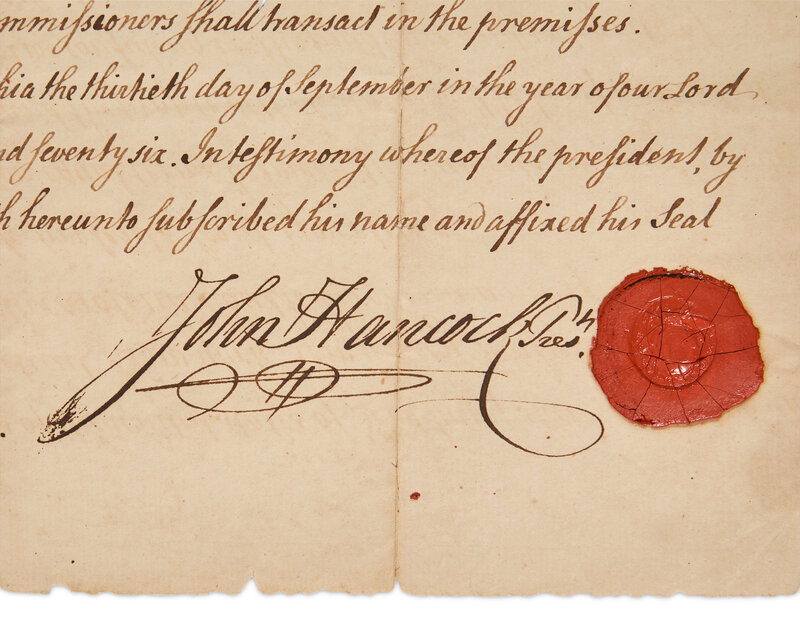

[American Revolution] Hancock, John. Manuscript Document, signed

The Seed of American Victory Over Great Britain: The Continental Congress Appoints America's First Envoy to France—Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Thomas Jefferson

Philadelphia, September 30, 1776. Single sheet, 15 13/16 x 12 5/8 in. (402 x 321 mm). Manuscript document in the hand of Secretary of the Continental Congress, Charles Thomson, and boldly signed by President of Congress, John Hancock, appointing Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Thomas Jefferson commissioners to France; counter-signed by Thomson. Red wax seal intact in bottom right; docketing on verso, "Commission to the Commissrs. Plenipoty. 30th Sept. 1776". Creasing from old folds, separations and small losses along same (affecting a few letters); small chipping along bottom edge; offsetting from seal in top right; light offsetting from text from when folded.

A document of great historical importance with far-reaching consequences in America's struggle with, and eventual independence from, Great Britain: the first letter of credence issued by the Continental Congress, appointing Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Thomas Jefferson commissioners to the court of France for the purpose of negotiating a treaty of alliance.

Newly discovered, this is one of only four known official copies of this letter of credence issued by Congress and originally signed by Hancock, the others being in the Arthur Lee papers at Harvard University, the Silas Deane papers in the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History (the latter with Lee's name in place of Jefferson's, and dated October 23, 1776), and in the Benjamin Franklin papers at the American Philosophical Society (the bottom portion excised and lacking Hancock's signature and seal). Three contemporary or later copies not signed by Hancock are also known: two in the American Philosophical Society, and one at Harvard University (the latter signed by Franklin, Deane, and Lee on the verso). According to Founders Online, "Thomas Jefferson's letter of credence, if sent, has not been found." (see Richard Henry Lee to Thomas Jefferson, September 27, 1776).

Declaring that "a trade upon equal terms between the subjects of his most Christian Majesty the king of France and the people of these states will be beneficial to both nations" this letter empowers Franklin, Deane, and Jefferson "to communicate, treat, agree and conclude with his most Christian Majesty the king of France, or with such person or persons as shall by him be for that purpose authorised, of and upon a true and sincere friendship and a firm, inviolable and universal peace for the defence, protection and safety of the navigation and mutual commerce of the subjects of his most Christian Majesty and the people of the united states; and to do all other things, which may conduce to those desireable ends, and promising in good faith to ratify whatsoever our said commissioners shall transact in the premisses."

On September 26, 1776 the Continental Congress selected its first ever foreign envoy, led by Benjamin Franklin, and aided by Silas Deane of Connecticut, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Jefferson subsequently declined the post in early October due to his ailing wife, and Arthur Lee of Virginia was chosen in his place on October 22. The creation of the official delegation was months in the making. Not long after shots rang out at Lexington and Concord, the American Congress began to debate whether to engage international powers to acquire much needed aid, munitions, and possible political recognition. Ultimately, as 1776 unfolded and the American army faced mounting losses and increasingly severe shortages of just about everything, Congress recognized that success against the better armed and more numerous British troops would only be feasible through foreign intervention. As Britain’s hereditary enemy, France was the most logical ally. With independence declared on July 4, 1776, Congress quickly set to drafting the terms of a treaty with her. While the proposed treaty was commercial in nature, Congress hoped that a military and political alliance would follow. The commissioners were authorized to amend the treaty as they saw fit, while also being tasked with acquiring weapons and other war materiel, much of which could not be manufactured in sufficient quantity in America.

When Franklin arrived in Paris in December 1776, he was welcomed as a celebrity—the symbol of America par excellence. His presence attracted all sectors of the curious French public eager to glimpse the "tamer of lightning." He was met by Deane, a Connecticut merchant who had been in Paris since the spring, tasked by the Committee of Secret Correspondence with securing munitions from the French Court and elsewhere. They were soon joined by Arthur Lee, the irascible brother of Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, who had been posted in London as the Secret Committee’s agent. As Walter Isaacson wrote, in Franklin and his two colleagues' hands had been placed "the fate of the Revolution.” What awaited these men was a yearlong, and at times frustratingly paced, diplomatic dance with the French court, then led by foreign minister, Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes. Progress proved to be slow, causing Lee to lament that the French, "talk much, do little, and protract everything". Although France desired to see Great Britain strategically weakened by the ragtag American rebels, they were not yet willing to openly support them, fearful of a full-blown war with Britain for which they were neither financially nor militarily prepared. Furthermore, until the rebels could prove themselves on the battlefield—very questionable as the multiple losses in New York in the fall of 1776 had shown—Vergennes and his ministers would watch and wait. Cautiously, the French did agree to provide some limited clandestine support, in the means of loans (upwards of 5 million livre by the end of 1777), munitions, and engineers, all the while turning a blind eye to American privateers that harassed British shipping and used French ports to outfit and trade.

Taking up residence in the Paris suburb of Passy, Franklin and company spent the next several months pressing the deflecting French court for a treaty, while themselves acquiring arms, securing financial aid, organizing shipments, outfitting privateers, plotting smuggling networks, and awaiting good news from the American front. Their work was troubled by a daily onslaught of French and European adventurers seeking high commissions in the American Army (despite their general lack of abilities and often burnished resumes--with the notable exception of the Marquis de Lafayette), and compounded by the surveillance of the French secret police, as well as a web of prying British spies who read their mail, tracked their movements, and disseminated mountains of disinformation. Despite this, the first shipments of war materiel began reaching America in the spring of 1777, and was followed over the next several months by vessels outfitted from Bordeaux, La Havre, and Dutch ports, who evaded the British Navy via the French and Dutch West Indies. This support was crucial in helping sustain General Washington and his army from dissolution throughout 1777, giving the Americans the chance to continue the fight for another day. The tide of war began to turn in America's favor in the fall of 1777 with their victory at the Battle of Saratoga, where nearly 6,000 British soldiers under the command of British General John Burgoyne surrendered. During this battle, about 90% of the arms carried by the Americans were French in origin, and nearly all American soldiers depended on French gunpowder. As historian James Breck Perkins wrote, "If Burgoyne's expedition had been successful, it is doubtful if France would have interfered in the American cause, and still more doubtful if the colonists, without such assistance, could have achieved their independence."

With the Americans having finally displayed their military abilities against the British, Franklin used their victory as leverage in his negotiations with the French court, alluding to a possible reconciliation with Great Britain should the French continue to drag their feet in recognizing the United States. Eager to prevent this, the French finally agreed to a treaty of commerce and military alliance, which was signed by both nations on February 6, 1778. Its 33 articles were generous, committing the French to protect American ships and make common cause against the British. The three-man envoy was formally presented to King Louis XVI at the end of March, and the welcome news reached America that April.

Over the next five years of war, French support was critical for the American army's survival and battlefield successes. Overall, the French would provide over 10,000 soldiers, aided by some 22,000 naval personnel on 63 warships, as well as an incalculable number of arms, gunpowder, flints, field pieces, cannons, uniforms, shoes, and other crucial wares. Almost immediately after signing the treaty the French began to attack the British Navy and her shipping, which was followed by naval engagements against prized British holdings in the West Indies, both of which critically siphoned off much needed British troops and supplies from reaching the North American front, and thus turning the war into a global conflict. French support was crucial at the Battle of Yorktown in the Fall of 1781, where the comte de Grasse's naval blockade and the comte de Rochambeau's ground troops, in coordination with General Washington, defeated the 8,000-man strong British army under General Cornwallis, thus ending major hostilities of the war. As Perkins stressed, “without French aid, the capture of Yorktown and of Cornwallis’s army would have been impossible“. Not including France's own expenses, by the end of the war in 1783, they had provided nearly 1.3 billion livres in aid to the United States, a staggering amount that tipped the balance of military power in America's favor, and which was vital for its emergence as an independent nation.

A document of historic magnitude, it represents not only the beginning of American diplomacy and nascent Franco-American relations, but the birth of the American nation.

This lot is located in Philadelphia.