Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 148

Sale 6465 - Printed and Manuscript Americana

Jan 29, 2026

10:00AM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$250,000 -

350,000

Price Realized

$371,200

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

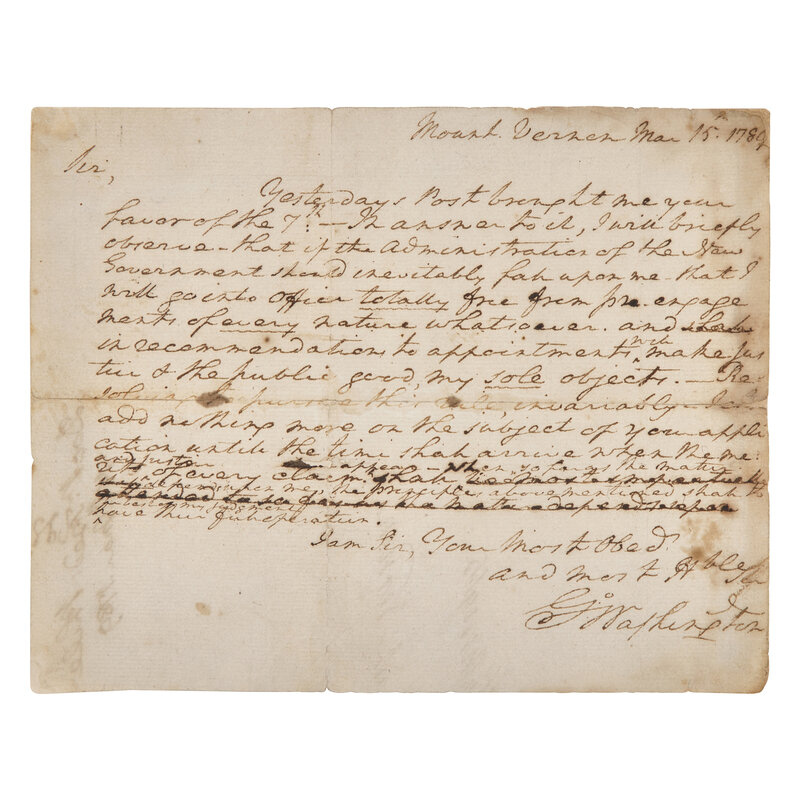

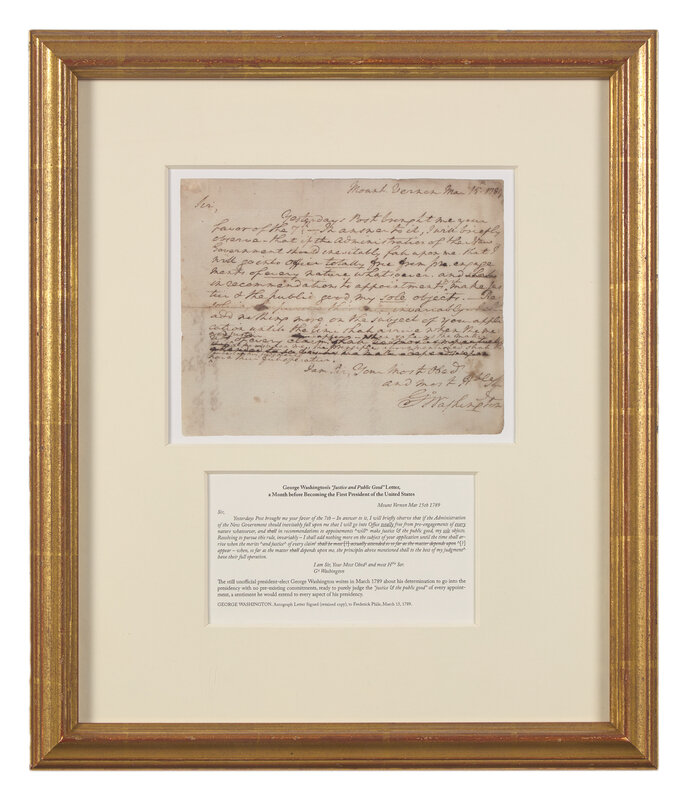

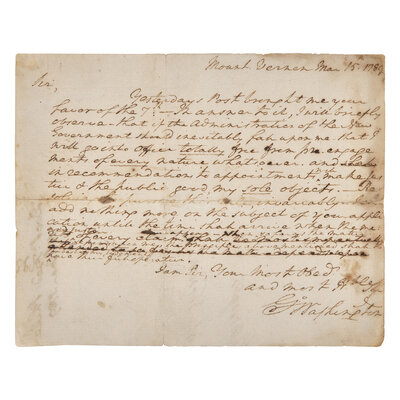

[Washington, George] Washington, George. Autograph Letter, signed

Father of the Nation, George Washington Pens His Philosophy For The Presidency, and His Dedication to Judgements Based On "Justice & the Public Good"

"if the Administration of the New Government should inevitably fall upon me...I will go into Office totally free from pre-engagements of every nature whatsoever, and shall in recommendations to appointments will make justice & the public good my sole objects..."

Mount Vernon, March 15, 1789. Single sheet, 6 1/2 x 8 in. (165 x 203 mm). Washington's own retained copy of his autograph letter, signed by the President-elect, to Frederick Phile, written on the excised integral leaf of Phile's March 7 letter to Washington (now in the Library of Congress): "Sir, Yesterdays Post brought me your favor of the 7th--In answer to it, I will briefly observe that if the Administration of the New Government should inevitably fall upon me that I will go into Office totally free from pre-engagements of every nature whatsoever, and shall in recommendations to appointments will make justice & the public good my sole objects. Resolving to pursue this rule, invariably--I shall add nothing more on the subject of your application until the time shall arrive when the merits and justice of every claim appear--when, so far as the matter depends upon me, the principles above mentioned shall to the best of my judgement have their full operation. I am Sir, Your Most Obedt and Hble Serv. Go: Washington". Docketed on verso in Washington's hand, "To Doctr Fred: Phile 15th Mar. 1789." Various emendations to text in Washington's hand. Creasing from old folds; scattered ink stains, especially at right margin; in mat and frame with a printed description, 18 1/2 x 16 in. (457 x 406 mm). Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754-1799, p. 20

An incredible and enduring letter of George Washington's characteristically succinct eloquence. As the President-elect he states his intention to lead the newly-founded federal government as a meritocracy, without pre-existing commitments and with an aim toward "justice & the public good."

Frederick Phile (d. 1793) was a Philadelphia physician who served as surgeon to the 5th Pennsylvania Regiment, from 1776-77. This letter is in response to Phile's request for an appointment as a naval officer at the Port of Philadelphia (Phile to George Washington, 7 March 1789, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, 1987, vol. 1, pp. 370–372.) Phile had been called a drunkard by some, but Washington received endorsements on his behalf from prominent individuals such as the Rev. Henry Helmuth, Col. Daniel Hiester, and Senator Richard Henry Lee. In the end, Phile was granted the position, and he served in its capacity until his death in the yellow fever epidemic of 1793.

Since March 1, 1781, the United States was governed by the Articles of Confederation, and while the system proved effective for a time, problems arose in the early years of independence that caused many in government to call for change. By February of 1787, the Confederation Congress passed a resolution for a gathering to be held at Philadelphia in September of that year "for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation." The ensuing convention resulted in the drafting of the new United States Constitution. Once ratified by nine states, the new system went into effect on March 4, 1789.

The Articles were characterized by a weak Federal government, which proved a main factor in favor of establishing the office of the Presidency. Some framers believed granting so much power to one individual would result in a new monarchy, however, a system of checks and balances were added to the three separate branches of government to quell concerns. Washington had been among those in favor of reform, and was critical of the Articles of Confederation throughout the 1780s, on one occasion referring to them as effective as a "rope of sand." When the Constitutional Convention first met in May of 1787, he was elected to preside over the meeting. His national prestige was key in lending the Convention legitimacy while also lobbying support for the government's ratification.

Washington was rarely occupied by advancing personal ambitions, and his diffidence towards power had been a recurrent theme throughout his life, first as a militia officer in the French and Indian War, and then as the Commander of the Continental Army. On December 23, 1783, after independence had been secured, he resigned as commander-in chief of the army, and was subsequently dubbed by many "The American Cincinnatus", and venerated as a living embodiment of republicanism. These key attributes made him the ideal candidate for the Presidency in many of the Founders' and Framers' eyes. Furthermore, the fact that he had no children of his own further allayed fears of a potential hereditary monarchy. With the office of President formally established, Washington was unanimously elected on February 4, 1789, the only instance of this in the history of the United States.

Despite the support from his contemporaries and the general populace, Washington was wary of returning to public office, especially in a role as consequential as the Presidency.

The language in Article II of the Constitution describing the Executive Branch was ambiguous in many cases, a fact Washington was well aware of from presiding over the Philadelphia Convention. The undefined nature of the role caused him to question his own fitness to lead in the post- Revolutionary era. The two men Washington arguably trusted most, the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton, were adamant that he was the only man for the job, and convinced him that refusing the position could jeopardize the success of the new government. This would prove to be the most persuasive argument for Washington, as his commitment to the new nation was steadfast, confiding that he would assume the position if "it be a conviction that the partiality of my Countrymen had made my services absolutely necessary..." (George Washington to Benjamin Lincoln, 26 October 1788, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, Vol. 1, pp. 70–74)

Six weeks after penning the above letter, Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789. He then immediately set out to form the roles of the Executive Branch as we know them today. His official actions were guided by his own Republican ideals, and he surrounded himself with a cabinet of highly renowned Secretaries to handle issues outside his specialty. Biographer Ron Chernow describes Washington's accomplishments as President "were no less ground breaking than his deeds in the Continental Army...As a former commander in chief, he was accustomed to the chain of command, and delegating important duties, but he was also accustomed to having the final say...he enjoyed unparalleled power without being autocratic. He set out less to implement a revolutionary agenda, than to construct a sturdy, well-run government..." (Washington, A Life, pp. 602-603).

At the end of his first term, Washington was weary of continued public service, and his health was declining. He would have liked to retire, but infighting between cabinet members, especially Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, stoked fears of partisanship forming within the government. Both men convinced Washington they would put aside their differences if he would serve another four years, which he did, being reelected in February of 1793. In spite of promises, Washington's relationship with his Secretaries continued to deteriorate, with Jefferson and Hamilton both resigning their positions during his second term. Dismayed by the growing partisan politics, Washington retired to Mount Vernon where he lived out his remaining days until his death in 1799.

Washington was aware of the importance his inaugural term would hold, and knew that his actions would set a lasting standard. He shared these sentiments explicitly with James Madison shortly after his inauguration, writing "As the first of everything, in our situation will serve to establish a Precedent, it is devoutly wished on my part, that these precedents may be fixed on true principles..." (George Washington to James Madison, 5 May 1789, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, Vol. 2, pp. 216–217). Washington's presidency would be characterized by setting many important and consequential precedents for the office: delivering inaugural addresses, appointing a Presidential cabinet, the use of executive privilege, limiting service to two terms, and most notably, a peaceful transfer of power.

In the present letter to Frederick Phile, Washington affirms his commitment to the sentiments later expressed to Madison. His response shows, with characteristic foresight, his steadfast belief that government actions should be dictated by matters of principle, and without the corrupting influence of bias. As such, this letter is one of the finest Washington letters still in private hands that encapsulates his idea of good republican government.

The finished letter sent by Washington to Phile has not been located, nor have we been able to locate any other drafts. The Library of Congress contains a letterbook copy, while Mount Vernon contains a photocopy.

Washington referred to the standard of "justice & public good" in writing only a few times (we can locate only two other examples, to Benjamin Harrison, March 9, 1789, in the Library of Congress, and to Francis Hopkinson, March 13, 1789, in the National Library of Russia). The present example is the only letter we have found to reach the market.

This lot is located in Philadelphia.